I don’t know about you, but whenever I buy clothes that are “sustainable” – aka my favorite jeans from Reformation that supposedly saved 500 gallons of water – I tend to feel pretty good about myself. Fast fashion has been on the rise ever since the birth of the internet. But since then, the world of fashion has been viewed as an industry based on obsolescence. Did I really need to buy yet another pair of light wash boyfriend jeans? No. I probably have 5 pairs. Did my perfectly loose on the legs but tight in the waist jeans really save our water supply? No. Wouldn’t there be more water if the jeans were never made? If I just bought another pair from a thrift store? Yes. According to Business Insider, the fashion industry currently makes up 10% of all humanity’s carbon emissions, is the second-largest consumer of the world’s water supply, and pollutes our oceans with microplastics.

I know what you’re thinking: the title of this article is inarguably boasting the efforts of environmental conscious clothing brands, yet here I am shaming the industry for deterring our planet. But at the end of the day, are people ever going to stop buying apparel based on current trends? Will they stop throwing away old clothes to make space for new, in-style pieces? Probably not. In conjunction with the rise of the internet and the mainstream use of social media, fashion will be an ever-changing and transformative cultural enigma. Although the idea of altering your external experience – and thus what you wear – to maintain a socially desirable persona seems irrational, I don’t see this first-world shared norm going away anytime soon. So, given society’s mounting emphasis on appearance and our declining environment, the sustainable fashion movement may just hold some purpose. If people are going to continue buying new clothes regardless of the environmental repercussions, why shouldn’t fashion brands be pushing for sustainable processes?

Over the last few years, our world has become increasingly more aware of our planet’s well-being and of the industries that have contributed to such widespread waste and pollution (like fashion). Thus, it’s no surprise that a lot of sustainable fashion and apparel companies have sprung up or have shifted their branding to be more eco-friendly. Elite fashion houses like Stella McCartney, Rag & Bone, and Mara Hoffman are discovering new and unique methods to producing garments and textiles. Uncovering innovative ways to repurpose, recycle, and reengineer fabrics. Luxury brands like Dior and Prada have even followed precedent, steering the runway with reformist production techniques and pioneering textile developments. Yet, despite the seemingly current trend of sustainability, these fashion brands were in no way the first to embark on an environmentally conscious mission. All the new sustainable apparel start-ups and the ecologically-changing fashion brands that we know and love owe a great debt to a radical environmental activist: the CEO and founder of Patagonia.

The Patagonia Story:

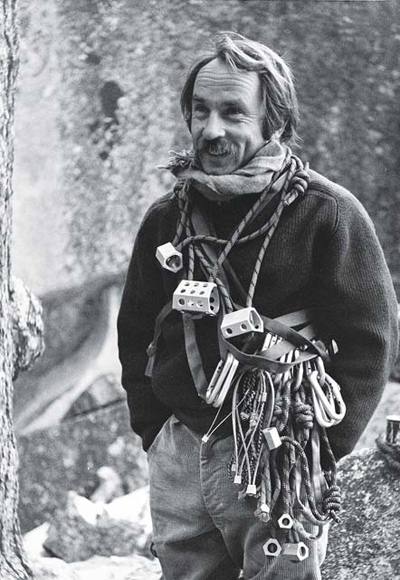

The year 1953 marked a momentous turning point for a seemingly normal 14-year-old boy, who was strung out with a sense of hopelessness at every hobby he acquainted himself with. This boy turned to the mountains and found a passion for climbing, feeling an abundant source of exhilaration each time he mounted the edge of a cliff and rappelled down and across its sides. This boy goes by the name of Yvon Chouinard, and he would later find himself to hold the esteemed role of being Patagonia’s founder.

After finding his newfound love in the mountains, he spent the next months and years travelling across America with his friends, searching for the most enticing and inviting peaks they could climb. His climbing soon transformed from a hobby into a way of life. As Yvon continued living for his awe of the outdoors, one thing struck him that he couldn’t seem to let go: his climbing equipment was damaging the surface of the rocks. He soon took this disgruntling thought, as he has always been hyper-conscious about the environment, and transferred it into the driving force that would define the philosophy of his first business, and later Patagonia’s. In 1965 Yvon and his like-minded nature-loving friend, Tom Frost, started Chouinard Equipment. Together, the duo redesigned and developed each element of a climber’s equipment. Their design standard was inspired by French Aviator, Antoine de Saint Exupéry, who voiced that “in anything at all, perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to take away, when a body has been stripped down to its nakedness.” As a result, their product offerings were the most durable, light, and simplistic equipment climbers could find in the market. And by 1970, their company became the largest supplier of climbing equipment in America. But something was wrong: their offerings were dismantling the rocks and causing severe damage, and in response to such damage, Yvon curtailed the business and set out on finding an alternative (which he soon did).

Shortly after, Yvon found himself adventuring to Scotland for a climbing trip, and during his journey he purchased a rugby shirt to wear on the mountains. As he reached the crux of his climb that next day, he realized that the shirt’s collars were protecting his neck from being painfully cut into by the hardware slings. He continued wearing this shirt and the trend soon caught on, his climbing mates asking where he got it and where they could purchase one themselves. This sparked Yvon’s action to create these shirts and sell them to climbers around the world under his Chouinard Equipment business. By 1972, their sales were skyrocketing. As the clothing side of the company continued to be met with unparalleled success, they decided this portion of the business needed its own name. And it was then, in 1973, that Patagonia was born, with Yvon Chouinard holding the reigns of the soon-to-be leading defender of environmental ethics in the activewear fashion industry.

Paving the Way for Environmentalism in Fashion:

Since the company’s launch, Patagonia has made a commitment to reducing their role as a corporate polluter. The company’s core values augment this promise, as they aim to “build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to protect nature, and don’t be bound by convention.” After years of research and design, they have now settled on the most efficient and non-depleting fabric yet: their Synchilla® fleece, a material made entirely from recycled polyester from soda bottles. Further, among their widespread array of patterned and colored activewear garments, they adamantly evaluated the dyes they use and eliminated any color from the line that mandated the use of toxic sulfides and metals.

By 1996, they reached a 60% reduction in energy at their distribution center in Reno, Nevada. They accomplished this feat in a variety of ways: by utilizing solar-tracking skylights and radiant heating; using recycled content for everything from rebar to carpet to the partitions between urinals; and retrofitting lighting systems in their current retail stores and buildouts for new stores. In that same year, they had met the goal they set for themselves in 1994 – to make their cotton sportswear 100 percent organic. Although this may not seem like a big feat given the current scope of fast fashion, Patagonia is nonetheless making itself a stepping stone for inciting change in the fashion industry. They are creating a community of consumers who push themselves to be skeptical of the companies they’re buying from, how those companies make their garments, and what affect this has on the greater good of our struggling environment.

Patagonia’s commitment to the environment stems far beyond their use of recycled materials and organic cotton. The company devotes itself to dedicating time and funding to the progressively evident environmental crisis. In as early as 1986, Patagonia had made the decision to make routine donations to smaller groups working to save or restore habitat. They began donating 10 percent of their profits each year to those groups, and later one percent of sales (profit or not). This action inspired the inception of 1% for the Planet in 2002, where members of this movement – both inside and outside the fashion industry – contribute at least one percent of their sales to environmental causes each year. Patagonia has also introduced a multitude of national environmental and educational campaigns, stemming from finding an alternative to a master plan of deurbanizing Yosemite Valley in 1988 to arguing for “dam removal where silting, marginally useful dams compromise fish life.” Patagonia became the first California company to become a benefit corporation, a legal framework that permits mission-lead companies to remain that way as they cultivate and change. They are also a Certified B Corporation, and to qualify as a B Corp, a business must “have an explicit social or environmental mission and a legally binding fiduciary responsibility to take into account the interests of workers, the community and the environment, as well as its shareholders.” In 2013, Yvon Chouinard formed a venture capital fund to aid start-up companies that weigh environmental and social outcomes with financial returns equally. However, Patagonia was no longer satisfied with lessening their impact on the planet. They wanted to start healing it. Yvon Chouinard took the first step by introducing Patagonia Provisions in 2012, which promotes sectors within the food industry that are equally indebted to being as sustainable and ethically aware as their fashion brand is. By late 2018, Yvon and Patagonia’s CEO altered their mission statement to reflect this goal: “Patagonia is in business to save our home planet.” In the grand scheme of things, Patagonia can’t save our environment on its own, but the company is setting new precedents for how fashion brands can truly make a difference. They’re inspiring consumers to think differently, and this change in consumer mindsets is pushing other companies and industries to feel pressure to act in similar ways.

Beyond caring for the physical environment, Patagonia carries a concern for the labor ethics within the fashion industry, and more specifically within their own supply chain. As the company does not directly own the factories that make their products, they have restrained control over how the factory workers are treated and how much they get paid. With their dual focus on the supply chain, Patagonia solely works with Fair Trade Certified factories in India, Sri Lanka, and Los Angeles. In enacting The Fair Trade Certified™ Sewing symbol, they’re assuring that a portion of the money spent on a product goes directly to the producers and stays within their community. To Patagonia, this is their way of pushing toward paying living wages throughout their supply chain.

Why We Should Care:

It may seem trivial to boast about one brand that’s making a difference. We all know that Patagonia isn’t the solution to the environmental crisis. But highlighting and celebrating this company holds purpose. Patagonia has constructed a fashion and lifestyle brand that inspires consumers and industries to change their behaviors. They have revolutionized a fad that makes caring for the environment cool. They have created a cultural and social shift in consumer and industry mindsets, moving them away from finding or making the best product at the best price to caring how it was made and what effect it holds in our communities and across the world. At a time where fast fashion seems to be conquering the globe, it is important to bring companies like Patagonia to the forefront of consumers’ minds. Companies with a commitment to bettering the environment have the ability to inspire corporate and cultural change, that who knows, may even lead to systemic change in regard to production and labor ethics. Is Patagonia and those like it an instant cure all? No. Are they important in a variety of subtle ways? Yes. Their mission and efforts can be a gateway in for people like me, the average consumer, to actually find meaning in a topic that can be overwhelming and alienating for a lot of us. Fashion in this mode is a stepping stone to igniting widespread change. There is a potential here that we often overlook, but together, if we center our attention and voice on appreciating and purchasing from brands like these, all companies may just follow suit.

By Bella Sprague